Richard Preston’s story

I was born in Cambridge,

Massachusetts, in 1954, and grew up in Wellesley, a suburb of Boston.

As a child, I was shy, and loved books. My dream was to be a starship

colonist heading for Alpha Centauri.

At around age 9, I got into books.

Books were an escape from shyness, and they opened doors leading into

worlds richer and seemingly more filled with wonders than my suburban

New England town.

In the afternoons I would ride my

bike to the town library, where I delved into Mark Twain, Robert

Heinlein, Madeleine L’Engle, Ernest Hemingway, Freddy the Pig, Arthur C.

Clarke, haiku poetry by the Japanese poet Basho … and I explored

science books, especially astronomy.

I’ve been fascinated with the natural universe ever since.

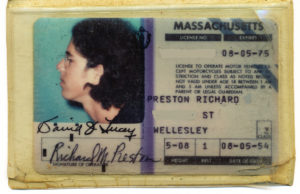

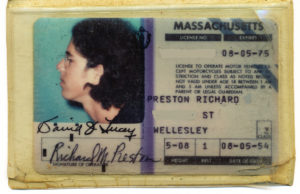

Here’s my first driver’s license, age 16.

My friends and I did a lot of aimless

driving around Boston in my beat-up Ford Falcon, occasionally picking

up a hitchhiker and gloriously driving the person to wherever they

wanted to go.

We went to rock concerts and

protests, and listened to music on vinyl records. (I stayed away from

drugs. LSD scared the daylights out of me.)

In high school, my record included

indifferent grades and an assault on a teacher during a protest. I

didn’t hurt the guy but I pushed him, and that’s an assault, for real.

I was suspended for weeks, almost expelled, and got something like 25

after-school detentions. I richly deserved my punishment.

Despite the trouble, I had some

outstanding teachers in high school. They included Jeanie Goddard,

Gerry Murphy, and the late Dr. Wilbury A. Crockett, [link

http://www.vqronline.org/essay/mr-crockett] the distinguished high

school English teacher who inspired his student Sylvia Plath to write

poetry.

I got rejected from every college I applied to. Afterward I sent an application to Pomona College. Pomona rejected me, saying my application was far too late.

After that I made a collect call to

the dean of admissions at Pomona. (In a collect call, you’d ask the

operator reverse the charges to the person you were calling—you’d make

the person pay for your call. A collect call cost around $20 back

then.)

So I called the Pomona dean of

admissions collect. He accepted the charges. I said to him, “Do you

have a policy where you change your mind?”

No, the dean said politely.

“What are the chances your policy could change?” I asked.

No chance the policy will chang, the dean answered.

After that I started calling the dean

once a week, collect. It cost him twenty dollars each time I called,

but he kept accepting the charges. “Hi dean,” I’d say. “Just checking

to see if your policy has changed.” No, it had not changed.

After paying for about five collect calls, the dean told me that the college’s policy had been adjusted with regard to me—but not changed. In fact, the dean had put me on the college’s waiting list. Then they admitted me.

I caught fire intellectually at Pomona College, majored in English, and graduated summa cum laude.

Later, I ran into the dean of admissions and asked him why he let me

into the college. “I just decided to take a chance on you,” he said.

One lesson is that (polite) persistance can pay off, and the other

lesson is that it never hurts to ask.

After college I went to graduate school at Princeton University, where I got a Ph.D. in English.

While studying for my doctorate at Princeton, I took a writing course taught by the author and New Yorker writer John McPhee.

In McPhee’s course I became fascinated with the idea that nonfiction

writing can be literature—nonfiction can be artistic, sophisticated

writing, writing which is powerful enough to explore any and all aspects

of human existence.

The novel, it seemed to me then, is

like a cathedral. It was created by masters and took centuries to

build. If you were to work on the cathedral of fiction today, you might

be able to add some pieces of beautiful stained glass to a window, but

you would probably not lay the foundations and build the arches and

towers.

Nonfiction narrative, on the other

hand, was something that seemed underexplored as an artistic form. It

was terra incognita for a writer who was interested in developing

different ways of telling a story.

My first book was a narrative nonfiction book about astronomy First Light, published in 1987. It is still in print and is considered a sort of cult classic about science.

Today I live in New Jersey, not far

from New York City, on a place where I climb trees with my children, for

fun. I do my writing in a small office at our place, and enjoy life

with my wife, Michelle Parham Preston, who is working on a book that I

think will fascinate readers when it’s published. We have three

children, all of whom are currently involved in writing and publishing.